(RNS) — The order got here on Feb. 21, 1939, seven months earlier than the beginning of World Warfare II. All German Jews, it said, “should give up any objects manufactured from gold, platinum or silver, in addition to valuable stones and pearls, of their possession.”

Most Jews complied, filling pawnshops throughout Germany with tons of valuable metals — a lot of which have been melted down and used to assist Germany’s struggle efforts. However a tranche of things survived, together with tons of of home items: Shabbat candlesticks, kiddush wine cups, spice containers, thimbles and many silverware, particularly spoons and ladles, which made their approach to museums throughout Germany.

AnnaMaria Abernathy, a Boston-area resident, knew nothing concerning the Nazi occasion’s “silver levy,” or “Silberzwangsabgabe.” However a couple of years in the past, she realized {that a} silver kiddush cup belonging to Friedrich Sigmund Marx may now be hers. Abernathy had an uncle by that identify, a former resident of Munich who died within the Theresienstadt labor camp.

Earlier this month, Abernathy, now 95, and her three daughters traveled to Munich for a convention placed on by Matthias Weniger, a curator from the Bavarian Nationwide Museum who was working feverishly to return these items of silver to the descendants of Jewish households who surrendered their heirlooms as a part of the Nazi silver levy.

The 76 members of the family who gathered in Munich got here from Australia, the UK, the US, Israel and Spain. All of them had kinfolk who perished within the Holocaust — folks like Abernathy’s aunt, uncle and grandmother, killed by the Nazis or their collaborators.

Quite a lot of the silver objects which were within the assortment of the Bavarian Nationwide Museum. (Picture by Bastian Krack/Bayerisches Nationalmuseum)

The members of the family on the convention had already acquired their heirlooms, however the Munich Convention on the 1939 Silver Levy and Reunion of Descendants was a chance for them to come back collectively and share tales. The group visited a cemetery and a Munich synagogue. They heard from consultants on the Jewish settlement in Bavaria and about what grew to become of all of the silver seized within the lead-up to the struggle.

“I believed it could be useful to convey households collectively and to speak about these widespread or related experiences and never be so remoted,” mentioned Weniger who heads the museum’s provenance analysis.

There’s an urgency to these restitution efforts. “You come actually near the final house owners in some cases,” Weniger mentioned.

On Thursday (April 24), Holocaust Remembrance Day, Israel honors the estimated 220,800 dwelling Holocaust survivors in over 90 nations around the globe, in accordance with a survey by the Claims Convention, a nonprofit that secures materials compensation for Holocaust survivors. These numbers are quickly dropping as extra survivors die annually.

AnnaMaria Abernathy, left, with Matthias Weniger, the museum curator and head of provenance on the Bavarian Nationwide Museum. (Picture courtesy of the Abernathy household)

The Bavarian Nationwide Museum is making an attempt to hurry up restitutions.

Starting within the Thirties, the museum was allowed to amass some 350 silver objects belonging to Jews. A lot of the items have been returned within the Fifties and Nineteen Sixties, when German authorities let it’s identified that folks might declare them. However about 110 silver objects remained.

Starting in 2019, Weniger took over provenance analysis on the museum and commenced actively on the lookout for the heirs.

The silver objects’ histories have been largely well-documented. They got here from pawnshops that listed the names of the house owners or had coded them in methods Weniger was in a position to decipher. Utilizing the inventories, and a very good little bit of detective work, Weniger tracked down the descendants by combing by obituary and family tree databases.

These prosaic objects weren’t Klimts, Picassos or Cézannes, paintings additionally confiscated from Jewish households by the Nazis and the topic of a lot media consideration through the years. However they have been intimately related to the on a regular basis lives of their house owners. Weniger made a number of journeys to the U.S. and to Israel to personally return the objects.

It turned out, the kiddush cup regarded as owned by Abernathy’s uncle belonged to another person. However by then, the rightful possession of the cup had grow to be secondary. Abernathy had already taken an amazing curiosity within the restitution venture and requested Weniger to assist her apply for memorial plaques for her grandmother, aunt and uncle. He was glad to assist.

Town of Munich has positioned 275 brushed chrome steel and gold-plated plaques known as Erinnerungszeichen on buildings and road posts, honoring the ten,000 metropolis residents who misplaced their lives in the course of the Holocaust. Abernathy and her daughters attended the plaque dedications together with different convention members.

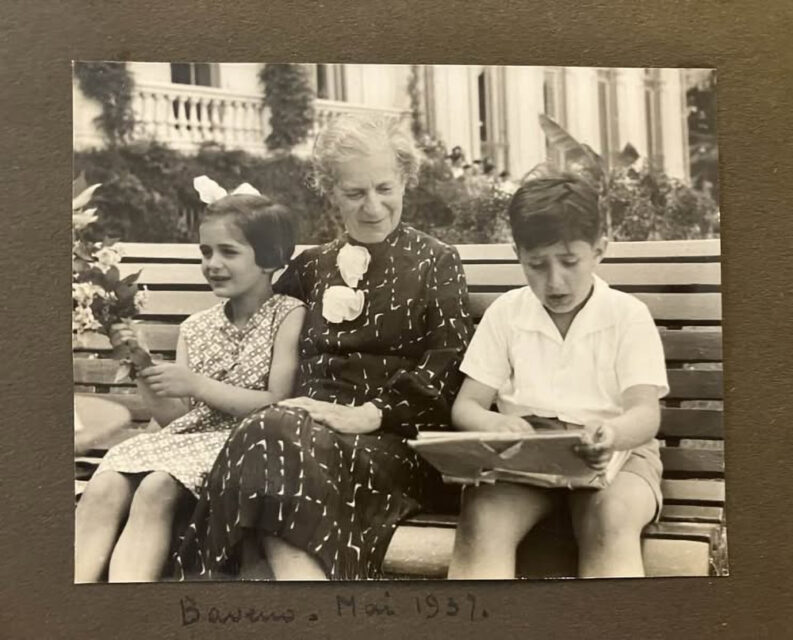

Minna Hirschberg, grandmother to AnnaMaria, left, and Charles, proper, in a photograph from 1937 in Italy. Hirschberg died within the Theresienstadt labor camp. (Picture courtesy the Abernathy household)

Abernathy was born in Germany, however in 1934, as the primary Nazi discrimination legal guidelines took maintain, her father, a banker, misplaced his job, as did many different Jews, and the household relocated to Italy. In 1939, months earlier than the beginning of the struggle, the household secured visas to the U.S. and settled in Kansas Metropolis.

Abernathy’s paternal grandmother, Minna Hirschberg, and Minna’s daughter Erna and husband, Friedrich, or Fritz, weren’t so fortunate. Minna and Fritz died in Theresienstadt; Erna was killed in Auschwitz. Affirmation of their deaths got here solely after the struggle.

“It affected my household very strongly,” Abernathy mentioned in a cellphone dialog from the retirement neighborhood the place she now lives. “I feel I type of blocked emotions about it.”

Within the Nineteen Sixties, Abernathy reconnected with second cousins on her mom’s facet, now dwelling in California, however then the households misplaced contact. Via the Munich museum’s restitution venture, she reconnected with them.

“Somewhat than receiving a silver object we didn’t know existed or belonged to us, we’ve acquired a present of gold in reconnecting our household,” Abernathy mentioned on the ceremony unveiling the plaques earlier this month.

Quite a lot of the silver objects which were within the assortment of the Bavarian Nationwide Museum. (Picture by Bastian Krack/Bayerisches Nationalmuseum)

As for the kiddush cup, it ended up going to a household that had fled Germany in 1939 and settled in New York Metropolis. Abernathy met the granddaughter of the cup proprietor on the Munich journey.

Gabrielle Rossmer Gropman’s grandfather, named Sigmund Marx, survived the struggle and made it to New York Metropolis in 1940 together with his spouse, Emma. The cup owned by the couple in Munich probably dates again to the seventeenth century. Gropman mentioned she determined the cup ought to go to her nephew who resides in New York Metropolis and has two babies.

Weniger has 20 items of silver left within the museum’s assortment, and he’s assured he’ll have the ability to return a dozen to descendants of the unique house owners. About seven or eight items will stay as a result of the descendants both weren’t inquisitive about reclaiming the objects or didn’t signal the paperwork.

Educated as an artwork historian in medieval and Renaissance artwork, Weniger mentioned restitution work has grow to be his true ardour.

“This work is so totally different and a lot extra significant,” he mentioned. “You can’t restore what occurred, however you may no less than contribute a bit. I feel everybody ought to do that.”

RELATED: When America turns into a wierd land